Independence National Historical Park

Independence Hall - South Side, originally uploaded by John H. Kim.

The Declaration of Independence was adopted in 1776 in this fine 18th century building in Philadelphia, to be followed in 1787 by the framing of the Constitution of the United States of America. Although conceived in a national framework and hence of fundamental importance to American history, the universal principles of freedom and democracy set forth in these documents were to have a profound impact on lawmakers and political thinkers around the world. They became the models for similar charters of other nations, and may justly be considered to have heralded the modern era of government.

Independence Hall - North Side, originally uploaded by mrkathika. Independence Hall was included as a World Heritage Site on the basis of Cultural Criteria VI in 1979.

Criterion VI. The universal principles of the right to revolution and self-government as expressed in the U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776) and Constitution (1787), which were debated, adopted, and signed in Independence Hall, have profoundly influenced lawmakers and politicians around the world. The fundamental concepts, format, and even substantive elements of the two documents have influenced governmental charters in many nations and even the United Nations Charter.

Liberty Bell. The Liberty Bell was forged in 1752 at Whitechapel Bell Foundry in England — the same foundry that forged Big Ben (the 13-ton and, ironically, cracked bell within the Great Clock of Westminster) and the bells of Washington National Cathedral.

According to historians, the Pennsylvania Assembly probably ordered the Bell in 1751 to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of Pennsylvania's Charter of Privileges, religious and political freedoms that the state had enjoyed since its founding. The Assembly asked for the biblical inscription: Proclaim Liberty throughout all the Land Unto all the Inhabitants thereof - Leviticus 25:10

The Liberty Bell was to hang in the clock tower of the Pennsylvania State House. The State House was later renamed Independence Hall, and the Bell — once known as the State House bell —was renamed "Liberty Bell" by abolitionists who adopted it as their symbol in the 1800s.

The Liberty Bell cracked soon after its arrival in Philadelphia and was recast (from the original metal) by local craftsmen John Pass and John Stow in 1753. Even that casting had problems, and the Bell that now rests in the display hall is the third casting.

Over the next century of continual use, a crack had begun to form that had to be filed down to prevent a jarring noise when the Liberty Bell was struck (the filing marks are still apparent today). In February, 1846, the Liberty Bell was repaired and rung in commemoration of George Washington's birthday. The repair is visible today as a wide jagged crack spanned in two places by rivets. While it once rang the pitch of E-flat, the Bell has not pealed since 1846. (from National Science Foundation Article)

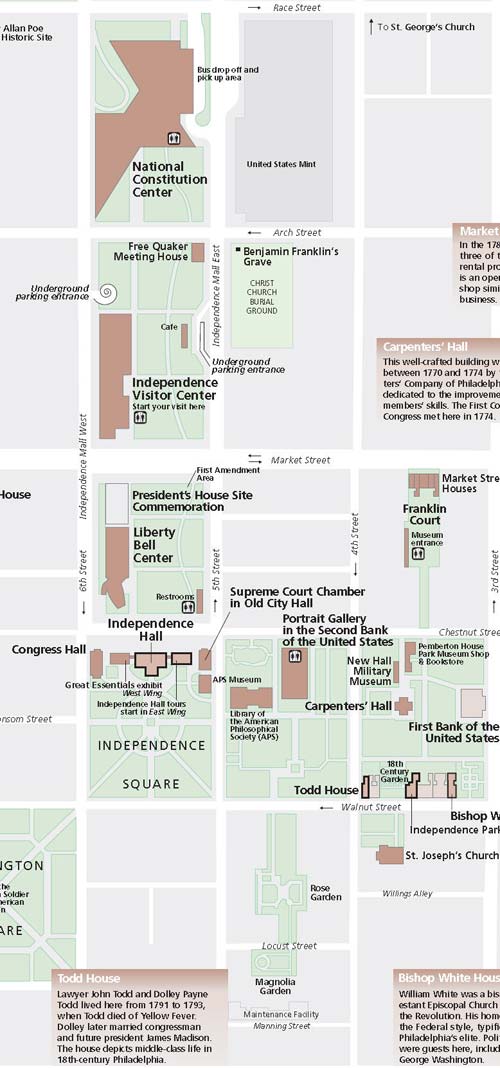

Independence National Historic Park Map - NPS (Click on Map for Larger PDF file)

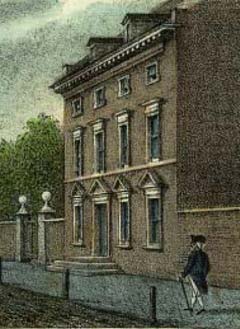

President's House Philadelpia by William L. Breton, c. 1830, from NPS Brochure.

President's House Philadelpia by William L. Breton, c. 1830, from NPS Brochure.

Congress Hall - NPS Photo

The President's House Site President George Washington called the elegant three-story brick mansion " the best single house in the city." Both Presidents Washington (1790-1797) and John Adams (1797-1800) lived and worked in this house, which was rented from financier Robert Morris. The site of this house is just north of the Liberty Bell Center. See the map above. (NPS Sign Excerpts)

Congress Hall is the oldest surviving building that was used by the Congress of the U.S. The House of Representatives met on the first floor. The Senate met on the second floor. Public galleries were built for both Houses. Originally, this building was the county courthouse, but it was loaned to the national government rent-free for ten years while the new capital, Washington DC was under construction. Philadelphia was the nation’s capital from 1790-1800. (NPS Article)

Congress Hall - NPS Photo

The President's House Site President George Washington called the elegant three-story brick mansion " the best single house in the city." Both Presidents Washington (1790-1797) and John Adams (1797-1800) lived and worked in this house, which was rented from financier Robert Morris. The site of this house is just north of the Liberty Bell Center. See the map above. (NPS Sign Excerpts)

Congress Hall is the oldest surviving building that was used by the Congress of the U.S. The House of Representatives met on the first floor. The Senate met on the second floor. Public galleries were built for both Houses. Originally, this building was the county courthouse, but it was loaned to the national government rent-free for ten years while the new capital, Washington DC was under construction. Philadelphia was the nation’s capital from 1790-1800. (NPS Article)

Independence Visitor Center - NPS Photo

Independence Visitor Center - NPS Photo

Liberty Bell Center originally uploaded by Payton Chung.

Independence Visitors Center is located on Independence Square at Market and 6th Streets. In order to see the inside on Independence Hall you must obtain a free, timed ticket at the Independence Visitors Center. There are also exhibits, and concierge staff to help plan your visit to Independence National Historical Park. Visit Independence Visitor Center for more detailed information.

Liberty Bell Center houses the Liberty Bell. It is open year round. The Liberty Bell Center offers exhibits and videos focusing on the history of the Liberty Bell and its role as a modern day icon.

Liberty Bell Center originally uploaded by Payton Chung.

Independence Visitors Center is located on Independence Square at Market and 6th Streets. In order to see the inside on Independence Hall you must obtain a free, timed ticket at the Independence Visitors Center. There are also exhibits, and concierge staff to help plan your visit to Independence National Historical Park. Visit Independence Visitor Center for more detailed information.

Liberty Bell Center houses the Liberty Bell. It is open year round. The Liberty Bell Center offers exhibits and videos focusing on the history of the Liberty Bell and its role as a modern day icon.

History of Independence Hall

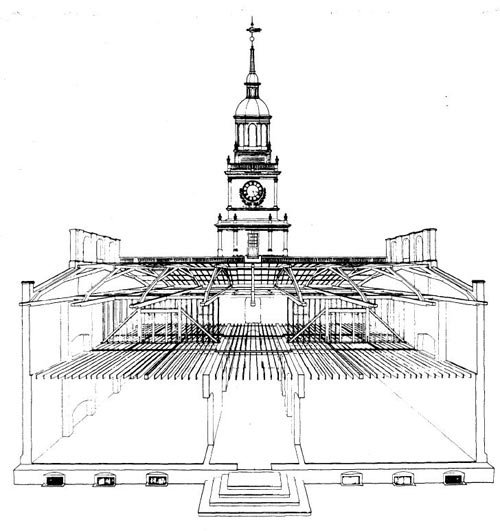

Independence Hall diagrammatic cutaway drawing ( from Chestnut Street ) showing the principal structural systems from Independence Hall World Heritage site nomination document.

Independence Hall's History

Independence Hall's history may be divided into four principal periods: service as the Pennsylvania State House, 1732-99 (during which time it housed the Continental Congress and the Constitutional Convention); use as a museum, 1802-28; service as a municipal building, 1818-95; and operation as an historic shrine, 1898 to the present. The structure has been subjected to a number of changes and several restoration efforts.

Andrew Hamilton, a prominent attorney, was the guiding force behind the building of Independence Hall as the State House for the Pennsylvania Assembly, or Legislature. As Speaker of that body, he sought to provide a dignified setting for its meetings, which had previously been held in private homes and taverns. Construction began in 1732.

Hamilton gained title to several lots in a block then on the town's outskirts, moved funding legislation through the Assembly, and brought forward the first of a number of plans for consideration. After much discussion and disagreement among members of the managing committee, the Assembly approved that advocated by Hamilton and the work commenced.

Insofar as is known, the design of the building was the result of Hamilton's overall architectural conceptions and master builder Edmund Woolley's ability to give them form. A gentleman with an interest in building and architectural design and a master carpenter no less concerned with these interests thus pooled their abilities to raise this important historic structure.

By 1735 east and west wings were added to the project, so the Province's administrative agencies might have offices at the legislative center of government. The structures were mere shells, but the Assembly occupied its unfinished chamber that same year. Before long money had run out, and in 1741 Hamilton died, leaving the project incomplete. In 1742 the Assembly Room was finally given its interior finish, and by 1749 the rest of the building stood complete, including an octagonal cupola on the rooftop.

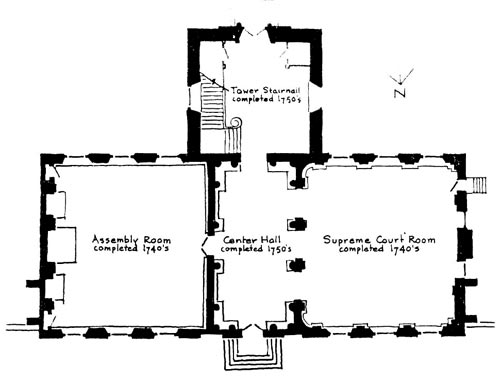

Independence Hall first floor sketch from Independence Hall World Heritage site nomination document.

In 1750, the Assembly ordered that a structure to house a new staircase and "a suitable place thereon for hanging a bell" be erected. Edmund Woolley again supervised construction. By mid-1753 enough of the steeple's work was in place to enable the new bell, bearing the inscription, "Proclaim liberty throughout all the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof," to be raised to its place in the lantern.

A library and committee room adjacent to the Assembly Room, as well as an oversized tall-case clock for the State House's west gable wall and a corresponding dial for the east gable, were added to the project. Devised by Thomas Stretch, the clockwork mechanism for both was located at the attic's midpoint; long iron rods turned the hands.

No other major modifications were made to the building before 1775, when the Second Continental Congress convened in the Assembly Room. The Congress met there off and on until 1783, after the end of the war. In that room it chose George Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, adopted and signed the Declaration of Independence, and functioned as the first national government. During the British Army's occupation of Philadelphia, in 1777-78, the State House served as a hospital, prison, and barracks, and suffered much damage.

Independence Hall Assembly Room where the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution were signed. Photo (1974) from Independence Hall World Heritage site nomination document.

When American forces regained control of the city, Congress returned to the Assembly Room. Late in 1778, the State Assembly remodelled the second floor to create a 40-foot-square chamber for their meetings until Congress should withdraw. The following year the Supreme Court Chamber was also remodelled. In 1781 the Assembly had the tower's wooden section removed, as it had rotted out and become a hazard. A low pyramidal roof and spire replaced the steeple. At that time the State House bell was repositioned in the tower's upper brick level.

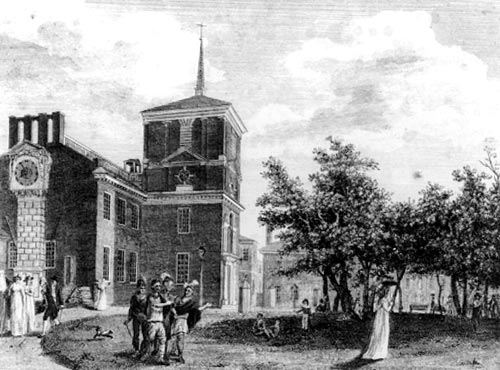

Engraving of the Back of the State House ( Independence Hall ) in 1799. The steeple had been removed in 1781 because it had rotted out and become a hazard. Engraving from Independence Hall World Heritage site nomination document.

Under the country's first comprehensive written frame of government, the Articles of Confederation, which came into effect in 1781, the Continental Congress continued to meet in the Assembly Room. Its tenancy came to an end in June 1783, after an incident involving the Congress and unpaid Pennsylvania militiamen.

The Assembly Room next served temporarily as a judicial robing chamber and for a time as a gallery for artist Robert Edge Pine. In 1784 alterations and general repairs were made, and the next year the Pennsylvania Assembly reoccupied its traditional meeting-place.

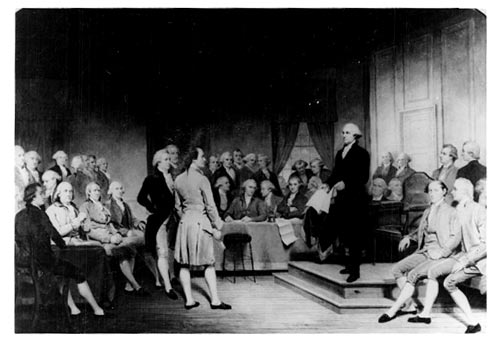

Once again, in 1787, the Assembly surrendered use of its chamber. On this occasion, the Constitutional Convention met to draw up a new frame of government for the American States. The delegates deliberated from May to September behind closed doors. George Washington chaired the sessions. Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, James Wilson, Gouverneur Morris, and Alexander Hamilton were among the luminaries present. After the signing of the document on September 17, the delegates departed and the State House reverted to its accustomed use.

Adoption of the U.S. Constition by Junius Brutus Stearns. Painting from Independence Hall World Heritage site nomination document.

When the Federal Government came to Philadelphia in 1790, the U. S. Congress met in Congress Hall, built in 1787-89, in Independence Square, at the corner of Chestnut and Sixth Streets, to serve as a county court house. By this same time, the State House Garden had been developed in the Square, and the American Philosophical Society Hall had been constructed.

In 1789 a change in Pennsylvania's government necessitated further alterations. The Supreme Court Chamber was remodelled to accommodate the enlarged bench of the appeals court. On two occasions during the 1790's the Supreme Court of the United States met in this courtroom, when quarters were not to be had in the City Hall Building (1790-91), adjacent to Independence Hall at Chestnut and Fifth Streets.

In 1799 the government of Pennsylvania moved to Lancaster and the next year the Federal Government moved to Washington, D.C. City and county officials continued to use the first floor of the Independence Hall for a while, and elections were held there, but the second floor had no occupant. Three years later, artist-naturalist Charles Willson Peale petitioned for the use of the State House as a gallery. His application was approved to the extent of allowing him the east end of the first floor and the entire second floor. He immediately embarked on a program of alterations, which was completed by midyear, and opened his museum by July.

Until 1812 the State House remained largely unaltered. Then, to answer a need for fireproof offices, the State permitted city and county authorities to tear down the wing buildings and the arcades that connected them to the State House, and replace them with two large office wings designed by architect Robert Mills. Henceforth, these became known as State House Row. Mills also demolished the committee room and library.

Next, the State decided to sell the State House to the city of Philadelphia. The governor signed the contract early in 1816, but the deed was not transferred until more than two years later. Since that time Philadelphia has owned the State House and its associated buildings and grounds. The city adapted the buildings in the square as a sort of civic center. In the course of fitting the Assembly Room for courtroom use, the wainscotting, Ionic pilasters, pediments, and entablature were torn out and replaced. The remnants were disposed of.

Public reaction to the changes in the building led to an attempt to restore it. Before then, the visit of the Marquis de Lafayette in 1824 had focused attention on the State House. Observances held in the Assembly Room emphasized its sad condition. Interest in restoring the building began to increase. Independence Hall thus became the object of one of the early American efforts at historic preservation.

Starting with the tower in 1828, the city rebuilt the steeple according to a design by architect William Strickland; took down the Stretch clock dials on the end walls of the main building; and installed four new ones on the second level of the new steeple.

After the death of Peale in 1828, the U.S. Marshall for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania leased the second floor of the State House for use as courtrooms and offices. In anticipation of this move, the city retained architect John Haviland to examine the building's structure and arrangements. With petitions on hand from citizens calling for restoration of the Assembly Room, the city councils requested that he consider ways of accomplishing that end.

Lacking substantive data to go by, Haviland chose to model his restoration of the Assembly Room on the Supreme Court Chamber. In doing so he harmed no one, though his work was to mislead several generations of visitors as to the original character of the room. Haviland's panelling, installed in 1831-32, would remain in place until the National Park Service began to restore the building.

For more than 20 years Independence Hall, as the building now became increasingly known, remained unchanged. The Federal courts moved out. Consolidation of Philadelphia City and Philadelphia County, in 1854, greatly enlarged service areas and government as well. The Common and Select Councils moved out of City Hall and into remodelled chambers that took in the entire second floor area of Independence Hall. Ceiling deflections were corrected, furnaces installed, and galleries erected.

Although the alterations of 1854 endured for 40 years, they meant better days for the Assembly Room. Following Lafayette's visit it had no assigned function, save for a brief period of use as a courtroom. Occasionally it served as a levee room for distinguished visitors to Philadelphia, and generally was "reserved as a sacred showplace for strangers." Antiquarian relics, including the Liberty Bell by 1852, slowly gathered there. In 1854 the room was renovated and recently acquired portraits from Peale's gallery were placed with the William Rush statue of George Washington.

Nearly 20 years more were to pass before Independence Hall again became the recipient of the Philadelphia councils' attentions to its historic associations. In 1872 they resolved that the Assembly Room be "set apart forever, and appropriated exclusively to receive such furniture and equipment of the room as it originally contained in July, 1776, together with the portraits of ... men of the revolution." A committee formed to this end and set about the restoration of the entire building. By 1873 the court of common pleas had vacated the Supreme Court Room, and replacement of worn and rotten woodwork was underway. Though no true restoration resulted, Independence Hall presented a bright appearance for the centennial celebration of 1876. In its wake, the so-called National Museum was established. Through the years, the museum gathered much artifact material related to the period of the American Revolution.

Yet another 20 years passed with the National Museum firmly ensconced on the first floor and the councils on the second. But in 1895 the Select and Common Councils moved to quarters in the new City Hall at Broad and Market Streets. For the first time in more than 150 years Independence Hall was no longer the scene of governmental operations. Now, the patriotic societies made restoration their goal. The Daughters of the American Revolution received permission to restore the second floor. They retained architect T. Mellon Rogers. Along the way the city became involved with restoration of the entire building.

Using the original drawings as a guide, Rogers attempted a restoration. While the second floor partitions were repositioned accurately enough, elements of architectural decor were highly inaccurate. In the Supreme Court Chamber he removed original entablature in order to lower the ceiling. He tore down the Mills buildings and replaced them with incorrectly proportioned imitations of the 1735 structures. The work of 1897-98, as the first overall restoration, happened upon but failed to record and interpret correctly much physical evidence of the past. Today's wing buildings and arcades remain from this restoration.

About 1920, the Philadelphia chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) began to take an active interest in Independence Hall. The restoration committee of the AIA took particular heed of structural weaknesses and strove to correct them with as little cost to the structure as possible.

In time the Hall came under the care of a city curator, who supervised operation of the National Museum and the other buildings on Independence Square as well. Guard and maintenance staffs struggled with the problems of maintaining an aging building visited annually by hundreds of thousands of people. The growing difficulties led to the organization of the Independence Hall Association in 1942. The association began to lobby for the creation of a national historical park incorporating the Independence Square structures and other important buildings and sites in Philadelphia.

Independence Hall is the nucleus of Independence National Historical Park. The structures and properties in the park, most of which are open to the public, include, among others, those owned by the city of Philadelphia but administered by the National Park Service. These consist of Independence Hall, Congress Hall, Old City Hall, and Independence Square, the plot of land on which these buildings are located. The American Philosophical Society holds title to Philosophical Hall, the only privately owned structure on Independence Square. All these structures are essentially intact originals. The exterior appearances of Old City Hall and Congress Hall have changed little since the 1790's. The interior of Congress Hall has been restored as the meetingplace of the U.S. Congress in the 1790's. Exhibits in Old City Hall relate to the activities of the U.S. Supreme Court and Philadelphia life in the same period. American Philosophical Society Hall is still the headquarters of the society. In recent years, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has created Independence Mall, a largely open landscaped area, in the 3 blocks directly north of Independence Square. The National Park Service administers it. The other major portion of the park, the three blocks directly east of Independence Square, has also been carefully landscaped. This area contains a number of historic structures from the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Most of these are in Federal ownership. Federally owned buildings in the park include the First and Second Banks of the United States; the Deshler-Morris House, operated by the Germantown Historical Society; Todd House; Bishop White House; New Hall; Pemberton House; and the Philadelphia Exchange. Among those privately owned buildings whose owners have cooperative agreements with the National Park Service are Carpenters' Hall, Christ Church, Gloria Dei (Old Swede's) Church, and Mikveh Israel Cemetery. These agreements assure the preservation and protection of the structures. Public Law 795, 80th U.S. Congress, approved on June 28, 1948, created the park "for the purpose of preserving for the benefit of the American people...certain historical structures and properties of outstanding national significance located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and associated with the American Revolution and the founding and growth of the United States" Its "administration, protection, and development" were to be "exercised under the direction of the Secretary of the Interior by the National Park Service." In furtherance of particular terms of the act, the Secretary of the Interior entered into a cooperative agreement with the City of Philadelphia on July 14, 1950, providing for administration and preservation of Independence Hall as a unit of the Park. Specifically, the agreement assured "access at all reasonable times to all public portions of the property," and that "no changes or alterations should be made in...its buildings and grounds... except by mutual agreement between the Secretary of the Interior and the [City of Philadelphia]..." The National Park Service assumed custody of Independence Hall on January 1, 1951. The building is in the charge of Park authorities and is open to the public every day of the year.

Most of the History Section's text is from Independence Hall's World Heritage Nomination Document.